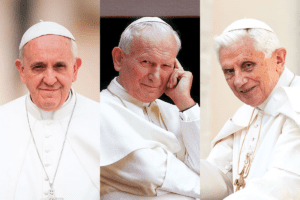

Season 2, Episode 7

In episode 7 of the Conversatio podcast, Dr. David Williams joins Dr. Ron Thomas, Fr. Matthew Schneider, and Patrick Novecosky to discuss St. Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict, and Pope Francis and their emphasis on body, mind, and soul.

- St. Pope John Paul II’s First Encyclical – Redemptor Hominis

- St. Pope John Paul II’s Second Encyclical – Dives In Misericordia

- Pope Benedict’s Jesus of Nazareth Collection

- Pope Benedict’s Introduction to Christianity

- Pope Francis’ Misericordia Et Misera

David Williams:

Welcome to Conversatio, The Belmont Abbey College Podcast, this podcast aims to form and transform our community so that each of us can reflect God’s image. I’m your host for this episode, David Williams, and today I’m joined by Dr. Ronald Thomas, and Father Matthew Schneider, professors of theology at Belmont Abbey College, as well as Patrick Novecosky, and award winning author, journalist and speaker, With a passion for the new evangelization, and Pope Saint John Paul 2, Thanks to all of you so much for joining us today before we dive deeper into our topic. I’ll let our guests more fully introduce themselves. Patrick?

Patrick Novecosky:

Well, thanks for letting me go first. I am. I’m honored to be part of the podcast. I am an author speaker. As you indicated, I wrote a book called One Hundred Ways, John Paul the Second Changed the World and had the Great privilege To meet him in person five times between 1997 and 2002 and spent most of my life as a journalist in the Catholic space, but also as a publicist, I’ve written for some of America’s most prominent Catholic publications: Our Sunday Visitor, National Catholic Register. I was the editor of Legatus Magazine for 15 years, and continue to kind of speak about John Paul the Second, and write about him. I’ve written for Fox News for the Stream for National Catholic Register, as I said, and a few others so happy to be here.

David Williams:

Fantastic thank you much, Father Matthew?

Father Matthew Schneider:

So my name is Father Matthew Schneider. I teach theology here at Belmont Abbey. I am a priest of the Legionaries of Christ. I was ordained in 2013. I just finished my doctoral thesis on privacy and I wrote a book on autistic prayer. I’ve also been a pretty avid commentator. Probably not as many articles as Patrick has, but a good number of articles in places like America, the National Catholic Register, Crooks, Aleteia, etc.

David Williams:

Very nice. And Ron?

Dr. Ron Thomas:

Yeah, I’m Dr. Ron Thomas and for about the last 15 years I’ve been professor of theology here at Belmont Abbey College and I’ve enjoyed it very much. I teach a wide range of students and classes, many upper level classes, things like liturgy and sacraments, theology of culture, the Virgin Mary, Christian spirituality, a number of things much. full disclosure, I am a convert to the Catholic faith having come from the Anglican Communion where I was a priest and I finished my PhD at the University of Cambridge in the UK and I’ve taught many places but as I say here at Belmont Abbey for about the last 15 years.

David Williams:

The time flies. I won’t say how long I’ve been here, but it’s a good place to be. Perhaps to get a started. We could do a quick intro on each of the three the three popes that we have under discussion, and the sort of lens for emphasis we’re taking on body, mind or soul. Patrick, Could you lead us off with Saint J. P. 2?

Patrick Novecosky:

Sure, yeah, John Paul the Second, I think, if you boil down the teaching of John Paul the Second, at its core is the dignity, the inherent dignity of each and every human being created in the image. In like this of God, he wrote about what he called the Mystery of Man of how and why God created human kind, Why, why? Creation? And he says that it’s mercy. At its core, God is mercy, And that God who needs nothing, created us as adopted sons and daughters to share in his divinity. And so he grew up. You know, He was a young man when the German Nazis took over Poland. He was a young seminarian priest when the Soviet Union began to rule Poland, and he saw the horrors of the twentieth century unfold Right in front of him, and through this time as a young philosopher, he’s pondering man’s inhumanity to man, and I think that formation helped to helped him, as he unpacked this idea of who we are as human persons, And that’s what gave us his great work, The Theology of the Body, and so much more, but you know, and being a father of the Second Vatican Council, he injected a lot of that into the writings of the Council, the documents that he was part of creating. And really, if you look through his teaching, Second Vatican Council, unpacking, the Council is in almost everything he wrote and said, and also this idea of the Mystery of Man, from the theology of the body all the way through to his teaching on where we’re going as a human race, Into the twenty first century,

David Williams:

The twentieth century is not an enviable time to be in Central Europe, by any stretch of the imagination, but

Patrick Novecosky:

Or anywhere on the planet, the bloodiest century in human history.

David Williams:

Well to stick with our European theme round. Would you do likewise for Pope Benedict?

Dr. Ron Thomas:

Yes, certainly. In one sense, that name Benedict says it all. Of course, this is the papal name that Joseph Ratzinger assumes when he is elected. In that name is embedded a real deep concern for Western culture, for Christendom as it historically had developed. Benedict carries a great burden Not only for his native Germany, of course everyone knows he’s from Germany, from Bavaria, but for the entire West, worried in many ways that we might be losing both our identity and our self-confidence. For Benedict, the confidence of Western civilization, of which he was proud, and justly so, was based ultimately in the Gospel. And he very much believed that those symbols still speak. He rather thought they had native power, and so he demonstrated that by wide ranging intellectual conversations with all sorts of people, including the people like Juergen Habermas and others. So that big concern for Western culture, all its symbols, all its works really animated him, sort of a hope for hope, a hope for faith, hope for recovery. I mean we could talk about him in the category of mind, I suspect, but he’s really quite far more than that. And as we roll the conversation, perhaps I can bring up some of the aspects of his mind that are not simply just intellectual matters.

David Williams:

Certainly, would have thought theology was an engagement for the whole person, and not just our heads. Father Matthew. What of Pope Francis?

Father Matthew Schneider:

Well, I think there’s a few things about Pope Francis. The first thing is that we’ve had, he was the 266th Pope and all 265 before him were either from Europe or the Mediterranean base and we had some from North Africa or Syria or Palestine and things like that. And so he comes from a very different kind of cultural background in that regard being from there, even though his family was Italian, so he wasn’t completely different from Italy. But I think with that, one thing is Patrick talked about the mercy of John Paul the 2nd. I think that was really a theme of Francis throughout his papacy has really been, you know, he had the year of mercy talks about like Jesus being the face of mercy, the, the, the relationship between mercy and justice a lot. And like John Paul 2nd talked about like the culture of life and the culture of death Pope Francis talked a lot about the throwaway culture in our modern society, where it’s just kind of everything is just tossed aside, you know, you buy it and then and you toss it aside, we have these huge piles of garbage, but we also have like that with human beings and how we treat human beings, just as objects to be tossed away. And so those would be some of the things. The last thing I would think to add really, is just a pastoral focus. Like right from about a few months after Pope Francis started the pontificate, I kind of made a comment that I still generally agree with, that I’d rather have Francis as my local pastor, but I’d rather have Benedict as my theology professor, I do think that he’s really good as that local pastor. And he’s not like, he adds something to theology, but he doesn’t have the breadth of Benedict in that regard because Benedict is absolutely amazing in that regard. One of the greatest theologians of the last few hundred years.

David Williams:

Absolutely. I think in terms of where to go next, what how do you think the emphasis characteristic of each man changed the church or the wider society? Patrick?

Patrick Novecosky:

Yeah, I always go back to John Paul 2nd’s choice for his very first encyclical Redemptor Hominis, and I’m just going to read you this quote that I just love. I think I’m going to print it out and put it on my wall. He says, “In Christ, and through Christ, God has revealed himself fully to mankind, and has definitely drawn close to it. At the same time in Christ, and through Christ, man has acquired full awareness of his dignity of the height to which he is raised of the surpassing worth of his humanity and the meaning of his existence.” So um, you know is pondering this today. I’ve written one book about John Paul the second, but I really think that as we’re coming up on this, this Eucharistic revival that the Bishops are talking about, that we need to go back and look at who we are as human persons in light of Christ, and his humanity, and his incarnation, And what that means, and how the human person is elevated because of Jesus decision to enter into history and to reveal himself fully. I’m also going through the catechism in a year with Father Mike Schmitz, and it’s really amazing how God reveals himself slowly through the course of history in time, and I think John Paul unpacked that very beautifully. There’s still so much that we need to unpack of who God is and who we are in light of the incarnation.

David Williams:

I think that that was certainly one of the emphases he stressed, and probably a good thing for the nineteen Seventies in the “Me decade” as we experienced it here. Uh Ron? What would you say for Pope Benedict?

Dr. Ron Thomas:

I’d like to just start with a contemplation about his role in the liturgy. He made a great number of waves early on in his career in Rome and later, of course, in his pontificate by calling to mind what we called the Hermeneutic of Reform. And this was juxtaposed to something called the Hermeneutic of Rupture. Yes, the reforms of the Second Vatican Council for liturgy were valuable and good when rightly understood but they need to be imbued with all kinds of reverence and all manner of art and excellence and So calling people back to this inheritance and in many ways he modeled that in his own way of dressing his own conduct of Vatican liturgies He really went up the candlestick, as you would say, about these sorts of things. And I think because he thought that, yes, this is our life of worship when theology does its best and has reached its limits, we adore. And so for him, I think the movement of liturgy was meant for adoration and for solemnity and reverence. And so he hoped that that spirit would suffuse all kinds of communities in the community of the West, this love of beauty, and so forth. Now, I’ll pivot here for just a second to highlight something I think is very important that people might be forgetting, and that is Benedict’s relationship intellectually and spiritually with St. John Henry Newman. I think if you want to understand how Pope Benedict is a different theologian, say, than a Neo-Scholastic or a Garrigou-Lagrange or someone like that. You might point then to Newman how it is that our knowing is a very capacious thing and it’s very creative. It covers many things. It’s not just propositional. It’s not just a scholastic or Aristotelian. God speaks in life and the human mind can know it and hear it and respond. And response is a huge word for Benedict, our response. And it’s very existential. So here again, so we have this idea of liturgics, then we have this new style of theology that you have in someone like Newman. You have existential response and then this love for the West. These things come out through him. Now, for my own purposes, I think of two documents, if I may just degrees for a second that really typify him. One is Spe Salvi, which is essentially, I believe this is first full sort of, you know, on his own of the encyclicals, this desire for hope. The other document, sort of controversial in its day, and it was written while he was still a cardinal, Dominus Jesus, Where the unity or what he called the unicity of the economy of salvation has to be taken seriously and with great confidence. So I fondly remember that encyclical, which of course was written in many ways for an Asian context but was very powerful in the West to get us all thinking along the lines of the kingdom and what we need to do to be able to witness to that. And of course if we do not have hope, if he says this love with a face, if we do not see that love with a face, we won’t have the adequate hope, right? To evangelize, to worship, to create, and to do all the good things that God has in store for us to do. So those two documents, at least in my mind, form sort of poles of some of his most important emphases.

David Williams:

I think it was very striking that he scheduled his trip to England while pope, specifically to beatified, John Henry Newman, to remind the audience that’s not something a pope would normally do. It’s the penultimate step to canonization to being recognized as a saint, so it was quite striking that he booked his England trip so that he could do that personally himself while he was there. It’s a signal evidence of how Newman meant to uh, and turning to Pope Francis, Father Matthew?

Father Matthew Schneider:

I think that there is starting off because Ron started off the liturgy. I think we can start off the liturgy for Francis as well in the sense that I think Benedict and Francis provide a kind of Two sides of the same coin in different aspects because Benedict tended to use like pull out all the nicest most Wonderful chasmal of things whereas Francis tends to use very simple ones much more plain ones emphasizing the simplicity of the liturgy, but I think there is a kind of constant tension in the Christian liturgy between the simplicity of the church. The church is not this rich, expensive, like a king or something like that, but at the same time we’re worshiping Jesus and he is the king, he is worthy of all that worship. So I think that there’s a nice balance between them. I think also another point that’s really come to the fore with Francis and changing it is that the church has gone back and forth between how centralized she’s being because there’s certain things in doctrine that are there but there’s a lot more that can be changed pastorally and how much you know you consult and things like that like after the second Vatican Council all religious communities had to implement much more of a Council so like my provincial if he wants to assign me to like when he assigned me to teach here had to get approval from like four other priests who are up there on his council whereas 75 years ago he would just decide that Fr. Matthew’s going to Belmont Abbey to teach. And the thing is that with that, is so Pope Francis with his Synod on Sodality and his emphasis on Synods, has really tried to bring it back from being overly the Pope, the Pope, the Pope, as the decision maker. And I think that that is slowly starting to change the church. And I think that there’s a healthy way to do it. Obviously, I think some people go way too far in that. And I don’t think Francis intends that at all. I still think he does intent, right, that this is a consultation, this is to help make decisions and things like that. And then I would say just that, again, that pastoral emphasis that he goes out, he does it, he, you know, some of the first things he did was like, hey, I’m going to go and serve the poor, I’m going to go and say mass for this, this, this local parish and things. If you remember the first week, the first weeks of his papacy would be like, he’d be going over here to say mass for this, you know, little parish enrollment things. I think that that that emphasis on that pastoral aspect and that common mission of the baptized, so the baptized participate is from the common priesthood in the church, and I think that that is being very helpful and it’s starting to have changes to really have the church not just sit there and think about Jesus, but really to have that encounter with Jesus, have that personal relationship with Jesus, and from that personal relationship that encounter makes the decisions that the church needs to make.

David Williams:

I think one thing about any pope, I think is that at the responding to the needs and circumstances of their day, but in doing so they also leave foundational elements behind that make more lasting contributions, and go on as part of the sort of the ongoing construction of the cathedral that is the Christian life. If here in 2023, where Saint John Paul Two has been gone for almost twenty years, Benedict’s papacy ended about ten years ago, and Francis is coming into his tenth year. What do us? It’s a bit early perhaps for Francis and Benedict, but what do we think their lasting contributions you could say to the Church or even the wider society have been.

Patrick Novecosky:

I’ll jump in with John Paul the second you know. Of course, his work with Ronald Reagan in ending Soviet communism in Eastern Europe, monumental shift, geopolitical shift in in the twentieth century, That legacy. I think it has sent ripples into the future that we’re feeling now in a very positive way. Not that we’re we’ve fully Kind of unpacked his teaching. In that regard, A lot of the documents. Actually that that transpired between Reagan and the Vatican are still classified interestingly, but I think that certainly from a diplomatic perspective made a huge shift in in the world. I think his teaching on the human person come back to that again. The theology of the body, George Wagnall called it a theological time bomb. I think there’s still so much there that we can unpack, as church again, understanding the human person, the dignity of the human person. You know, we’re seeing still incredible amounts of numbers of Christians being martyred all around the world, particularly in Africa in our day, Um, you know just this understanding of the human person, Uh, that that dignity of the human person, from the unborn all the way down to the elderly is something that I think John Paul the Second taught well, but hasn’t been unpacked well. Well enough, I mean, there’s just more work that needs to be done and in teaching that

David Williams:

Theology gives one a terrible sense of time, because the Council ended 60/50 odd years ago. It’s pretty clear. probably that Pope Francis will be the last pope to have memory of the council as a as an adult in the church, and of course, both Benedict and J. P. T 2 were there in different capacities, but feels so long to us. But in theology time were still in the immediate post conciliar period. Uh, and it’s interesting to think about all that gelling together from their contributions. What of Pope Benedict?

Dr. Ron Thomas:

Okay, at the beginning of the conclave, he used a phrase that, according to most commentators, would seal his doom and the reason he would never be Pope, and that was the phrase, the dictatorship of relativism. And of course, we know that he was elected pretty quickly. In many ways, I think that represents his enduring facet. He was a very keen analyst and critic of culture. And I don’t think that his culture critique is going to go away anytime soon. I think that in all of those books that he writes about Europe and culture and things like that, what he highlights as areas of strength and weakness, of possibility and danger, I think those things will just be intensified. So I think that ultimately, down the road, we will see that Pope Benedict was a linchpin kind of figure in the history of the West, offering words of warning and words of encouragement. We don’t know what tomorrow will be like, but I would be very surprised if his particular interventions in our common mind didn’t just grow with strength as the decades rolled on.

David Williams:

In a very Benedictine way you put the roots down and the tree grows over a larger expanse of time. Of course, Pope Francis is still in process, but if you follow Vatican news, He’s after ten years that people begin writing these forecasts and all these things. So what can we say of him? At this point,

Father Matthew Schneider:

Well, I think yeah, you’re right. He’s just he’s at 10 years I think I don’t think he’ll have nearly like the geopolitical impact of like a John Paul II. I just think that that’s you know that’s not where he’s being focused. He’s been focused I think much more on the church itself and I think two things that he’s talked about with the church I think we’ll have a lot of we’ll have hopefully a long-term impact in a good way one is he’s talked a lot about like the church being navel gazing and pointing inwardly and it’s really kind of a the problems put out in Gaudium Et Spes in Vatican II. And I think hopefully that that kind of perspective will change to help us realize, hey, we’re called to evangelize the entire society. We’re not just called to sit here and be, oh, I go to Mass on Sunday and things. And the other thing is related, and that regards when we talk about how the church makes decisions and how things happen, even at like a parish level, because this whole emphasis on that communal decision making and things like that, I think are going to be helpful to really bring things in so that parishes are not in local parishes even. Everyone is helping in that sense because I know as a priest I experienced a lot of times you go to a, you’re at a parish, a priest at a parish, he’s like, hey, we need, you know, everybody kind of looks at the priest, what do we want to run? What do we want to start at the parish? And really what Francis is saying is, wait a second, you are baptized people you should be thinking ok, and do we need a bible study? Do we need this group to go and serve the poor? We need like some, what groups do we need our church. And we, and all the people as the lay people, as the baptized people of God, should be putting forward our effort to start those, our effort to start that initiative and not just kind of looking to the one in charge and waiting for him to make all the decisions in that regard. And I think that that, that that mode of decision making, that mode of action could be a huge benefit for the church. So it’s not all just, okay, what does the Bishop here decide what does the pastor decide? But lay people take that initiative and bring forth the gospel in their own lives.

David Williams:

I think that’s a big part of the sodality process rightly understood, and in some ways I almost wonder if Francis is concerned with that and doing things like extending it to two sessions instead of one is to sort of get the process home as much as anything it may do. Substantively that it’s not coaling and it’s not parliamentary votes. But more of you’re talking about,

Father Matthew Schnieder:

Yeah, and I think that and at least to me that’s one of the things I would really hope for at a local level is like the pastor don’t just look at the bishop. Oh, what kind of initiative do we have in the in the diocese instead of think, okay, what do I do? The lay people don’t just look to the pastor and say, okay pastor, what are we going to do? But have their own initiative and go forward. And also that, you know, with that consulting, right? Like I’m a religious here. And right, so I was offered a contract to teach here for being a professor and so I went to my provincial and said I propose This as my assignment and he went to his council and they talked about it And they said yes, that seems right You know you did your doctoral thesis of the intention of teaching at a Catholic college And this is a good Catholic college to be teaching at so we’re we are you know But it’s that communal decision-making isn’t just it isn’t just the provincial just deciding oh Without any consultation with wherever and just say oh you go and do this and things like that Even though obviously with obedience if he tells me hey go and do that. I’m going to go and do it of in religious life now it’s very encouraged to say hey like the provincial asks you once a year twice once a year once or two years hey where do you see yourself in a few years what kind of assignments you think you do well so that they have your perspective as well and not just kind of what I think is the provincial.

David Williams:

And I think that’s a nice Segway to our next question because of course we can, and with a bunch of theology teachers and theological writers here, I think we can all do this a little too much. But how do we turn to that? What? how should we be taking the different emphases in teaching of these three figures And make it operational in our individual lives or circumstances, And we can go back to Patrick and look, look to Saint J. P. 2,

Patrick Novecosky:

Rephrase the question for me. If you will, David.

David Williams:

What we can talk about the emphasis and concerns of each man in his time, and we can sort of focus them like lenses under ideas of body or mind or spirit, But our audience today is all living in 2023, And what should what do Think We should highlight for them as points of particular interest as people living in this world of ‘23. From these figures we’ve been talking about,

Patrick Novecosky:

Yeah again, I’m coming back to J. P. 2 and his teaching the dignity of the human person. I think I think John Paul the Second focused so much on the dignity of the human person, not only because of his own experience, but he understood that if you get the human person right and you get our relationship with God right, then most other things will flow naturally from that. So my, my thought is that You know if we get human dignity right if we understand if we’re able to teach and convey the idea of a loving God, a merciful God that you know, just essentially Christianity 101 Um, you know, Go back to the Baltimore catechism. What’s the meaning of life? I just mean to know him, love him, and serve him in this life. Be happy with him forever in the next. Um, really that simplicity. If that’s ingrained in us, and we live that we start to live that in a healthy family situation. Then other things kind of just flow naturally from it. They make sense from that basic idea of the human person.

David Williams:

Ron?

Dr. Ron Thomas:

Yeah, I think you asked the question, how do we make it operational? I think Pope Benedict would really not like the phrase, make it operational.

David Williams:

Probably

Dr. Ron Thomas:

I mean, in many ways, one of his worries about us was that we think we make things. In fact, though, we are made. We’re made by God, informed by God. And so our making is not as important as our being made. I think perhaps one of the surprising, enduring things about Benedict’s work will be his work on Scripture, his stuff having to do with the Jesus of Nazareth series and things like that. That might be one of those areas where his thought bears fruit for a long time to come in very practical situations, in the minds of lots of laity and lots of clergy to go to the scriptures and see, in fact, Jesus Christ, bodying himself over to us through them. I think he’s given us in his scriptural work a great deal of a confident basis to make the Bible our own and continue to do that for as long as we are around.

David Williams:

As someone whose own academic work involved a lot of dealing with scripture? I can certainly say that the situation I can agree with that. The situation is much different now than when he started doing these kinds of really writing in the area in the 1980’s, and after, Uh, Father Matthew?

Father Matthew Schnieder:

I think I did a lot of Pope Francis’s mission is really being like I said the pastoral and bring that on the pastoral aspect and I think sometimes he tries to lead by example more than by Declarations in such right like he goes he goes to say mass In the prisons like when he goes to visit he came here to the U.S. He visited Philadelphia He went to say one of his mass in the prisons He often says the holy Thursday liturgy in the prison near Rome and things like that and the idea of going to those peripheries and doing it in his own life, not just talking about it. And I think it’s a good way of how he’s tried to do it. He’s tried to do it in that way because he does emphasize that going to the peripheries, but then he actually goes and does it. And he does actually bring, I think a lot of the ideas of John Paul II and Benedict and tries to put them in practice as an example and tries to kind of live them out and show the Pope as example instead of like the Pope as teacher, if that makes sense. And I think that that could be a helpful way to look at how Pope Francis adapted a lot of these things.

David Williams:

Very good, we will be coming up on our time shortly. But perhaps if we could check out, one should always leave the audience with a bit more. What is the one place or a text that you would leave the audience with? If they want to learn more,

Patrick Novecosky:

Well, gosh, there’s so much about John Paul the 2nd. What I would point him to probably is his first two encyclicals. Devizni Misericordia, his great encyclical on Mercy and Redemptor Hominis, Just two, And these are works that he was working on as books leading into his papacy. So things that he brought from the Council that he wanted to emphasize. You know Jesus in his saving work, and his incarnation, and what that means, And then Jesus as Merciful redeemer, Jesus as the Merciful one, and this time of mercy, you know he, He said, that God placed him in a particular place in time, and it was his task in Providence to be an essentially the one who shepherded Faustina’s teachings, brought them to The world. Worked on her canonization cause, ultimately beatified and canonized her, and that this is a time for mercy. And I really believe that this time for mercy that Jesus explained to Faustina is, is limited. That there is a time for mercy. Then will come the time for judgment, whether that’s the particular judgment at the time of death, the ultimate judgment at the end of time. But we have to understand that Jesus came and revealed himself to humanity in the incarnation, but he also came to Faustina, in this private revolution, to just kind of make sure that we’re not forgetting that ultimately God is mercy, and that his greatest attribute is mercy. So I think that really is key to John Paul the Second’s teaching that came early on, but also kind of worked its way into the other aspects of his teaching.

David Williams:

Very good. Ron?

Dr. Ron Thomas:

Yeah, I’ll go back to the Jesus of Nazareth scriptural divinity of Pope Benedict as a place I think where people should launch out into the deep with him. I think that would be very useful. For those who are of a more, you might say specifically theological cast of mind or even philosophical cast of mind, you’ll definitely though want to migrate back to that classic Joseph Ratzinger wrote early in his career and pretty much stood by his entire life. And the importance of that would be to help us know that yes we do have doubts and we are surrounded by doubt. Yet there is security in Christ and there is hope even for the misled and in many ways confused culture in which we live. And so the advanced students should definitely go back to that and try out their theological chops on that.

David Williams:

Sounds good, Father Matthew?

Father Matthew Schnieder:

I think one text of Francis that gets overlooked a lot of times is his decree on the year of mercy, is it Misericordiae vultus, the face of mercy, in that sense. And I think that that’s a, it’s a relatively short text, it’s not that long, but I think that’s a valuable text in his emphasis on mercy. And it’s a text that kind of just gets overlooked. And so among his other writings, and I think it’s a text that really deserves a lot more attention than it gets.

David Williams:

It’s certainly one of his major emphases And Lord knows all of us can do more mercy for both ourselves and in our dealings with others. Uh, well, I think that brings us to our close for today, and although Conversatio, the podcast series will continue, we are probably up for this moment, so let me just thank each one of you for Taking the time to be with us today, and we’ll Ask the audience to look forward to our next episode.

About the Host

Dr. David Williams

Vice Provost for Academic Affairs and Dean of Faculty

Dr. David M. Williams is the Vice Provost for Academic Affairs and Dean of the Faculty at Belmont Abbey College. After earning doctorates in Political Science and Theology at Boston College, he came to the College as a member of the theology department in 1999 before going into academic administration in 2014. Dr. Williams is the author of the book Receiving the Bible in Faith: Historical and Theological Exegesis, published by The Catholic University of America Press, and often speaks on theological topics or as part of diocesan programs.